Exploring the Design of Contemporary Tetris

In wake of live service business models, videogames are a product of time; disposable to most consumers. Despite the preservable nature of software, production and technical decisions are consistently made such that games are never frozen in time. Creative visions change, profit margins must increase. As a result, games metamorphose under the scrutiny of different executives and producers.

When a live-service game updates or shuts down, the previous iteration of the game is lost permanently. Gameplay mechanics are adjusted for balancing, the artstyle and tone of the game’s setting shifts (often for the worst). And, to facilitate it all, these games require players to have a constant online connection to their backend. One such notorious example of a game’s artstyle being compromised is the addition of Beavis & Butthead to the once serious, gritty franchise: Call of Duty.

Really, pointing out the gradual, permanent change of games overtime only requires one to observe the live-service industry as a whole. Meaningfully researching the evolution of games demands a more purposeful scope and a more consistent franchise to scrutinize.

Using Tetris as a case study allows for a micro-market analysis of product saturation, governing bodies, and the continual iteration of a product as it’s exposed to saturation. We can also look at Tetris’ evolution from a puzzle, score-attack game to one speed and artistic prowess.

Tetris is a franchise with over 200 officially licensed versions since its initial debut in 1988. Because no Tetris title has ever significantly adapted the live-service model, each entry acts as a time capsule of the business priorities and creative philosophies that went into it.

One layer deeper, The Tetris Company (previous Blue Planet Software), acts as a gatekeeper to obtaining a publishing license. To be granted a license, developers must adhere to a strict set of guidelines. While designers have a great deal of control over the visual presentation of their Tetris game, the technical implementation of Tetris’ game mechanics must be consistent with The Tetris Company’s expectations.

Thanks to the leak of the 2009 Tetris Guidelines, we get a pretty clear picture of the control afforded to the licensor. In pursuit of standardizing Tetris, rifts across design philosophies make themselves apparent. At the forefront of this is the drastically different gameplay of Tetris games released before and after the year 2000.

Colloquially defined as Classic Tetris and Modern Tetris, there are many differences across basic game functionalities transitioning from the 20th to the 21st century. It’s supposed simple changes from randomly assigned pieces to a 7-piece bag system, introduction of hard drops, and a formal declaration of how tetriminos are rotated, took Tetris from a game of emergent strategy to one of calculated play.

Watching competitors play Modern Tetris compared to Classic Tetris demonstrates this well. Classic Tetris emphasises forward thinking as players are not guaranteed dependent pieces within a certain range. Using 1989’s Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) Tetris as an example, the Delay Auto Shift (DAS) mechanic quickly becomes unsuitable for moving pieces across the board the game scales to speeds intended to be impossible to keep up with. It’s important to note that determining Classic Tetris to be unpolished is too reductive for in-depth discussion.

Modern Tetris aims to make players acquainted with each and every Tetris title, regardless of who developed it. When getting a desired piece in the near future isn’t enough, the ability to hold pieces allows for intricate setups. DAS now scales with game speed. Coupled with mechanisms to delay tetriminos locking together, players are empowered to disengage with the fatalistic nature of Classic Tetris.

Most competitive Tetris is played against other players. Not in the NES Tetris sense where players merely compete for a higher score but rather they can influence each other’s boards through the use of garbage. As players race to top out their competitors' boards, speed becomes the defining factor of the game. And, courtesy of the bag system, players are never challenged beyond pattern recognition to enable additional speed of play.

With only so much design space to work with and a looming monopoly presented by The Tetris Company’s licensing practices, it’s unsurprising that many unlicensed iterations of Tetris have taken shape. Independent developers remarketing Tetris’ appeal highlights that Tetris is no longer a franchise but an entire genre to develop under.

TETR.IO’s vision of uncompromising speed and flexibility wouldn’t be possible under the Tetris Guidelines’ restrictions. It’s not as though TETR.IO can’t play like other contemporaries but that its exhaustive list of customization options make it difficult to approach for casual players.

It’s obvious to say that unlicensed Tetris titles can innovate on the formula to a greater degree. This begins to claw at the bigger question, “How does Tetris convince players to keep buying new Tetris releases?”

The multiplayer, competitive business model incentivizes would-be dedicated players of a particular release to migrate to the latest and greatest as play counts dwindle for aging games. Unlike NES Tetris where your skills in singleplayer translate very well to competition, online multiplayer requires constant honing of one’s skillset. Making Tetris a habit and part of the player’s life is easy when not playing Tetris leads to the degradation of player skill.

Other entries with a lack of focus on multiplayer can either market themselves via art direction or the occasional derivative mechanic The Tetris Company allows through their desk. Games like Tetris Effect or Tetris: The Grand Master (TGM) capture parts of the market that don’t align with competitive Tetris philosophies.

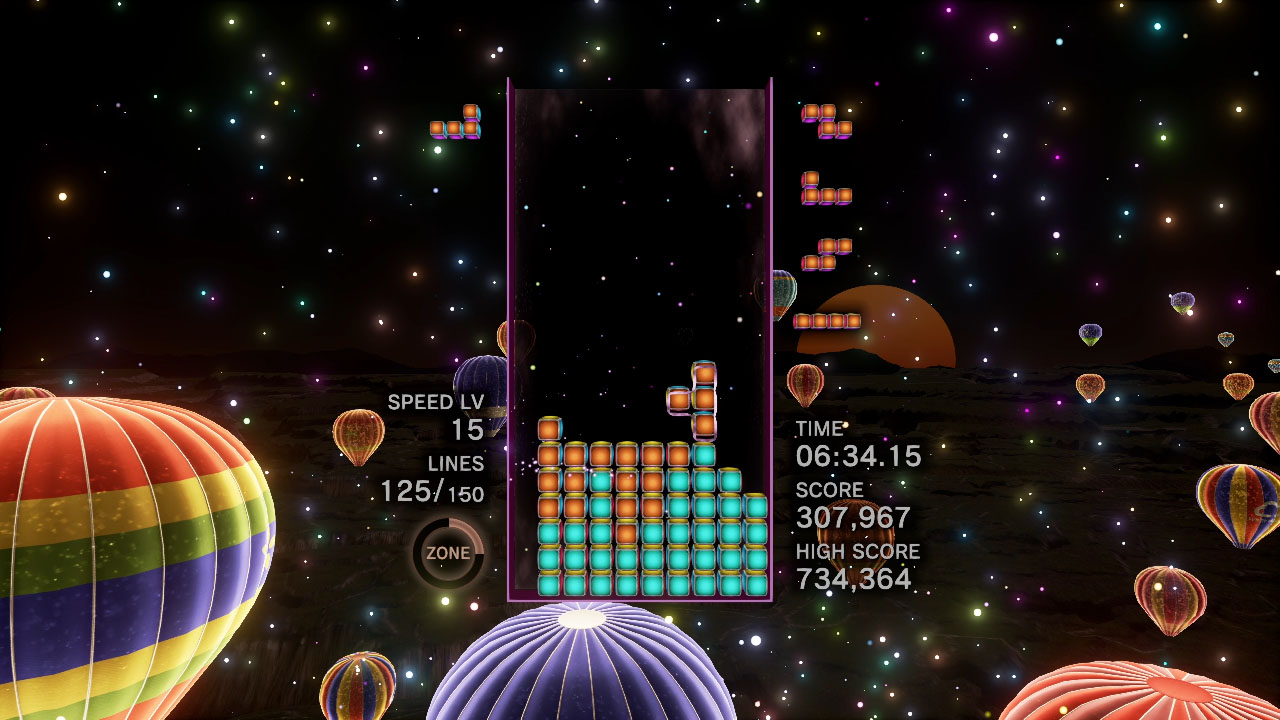

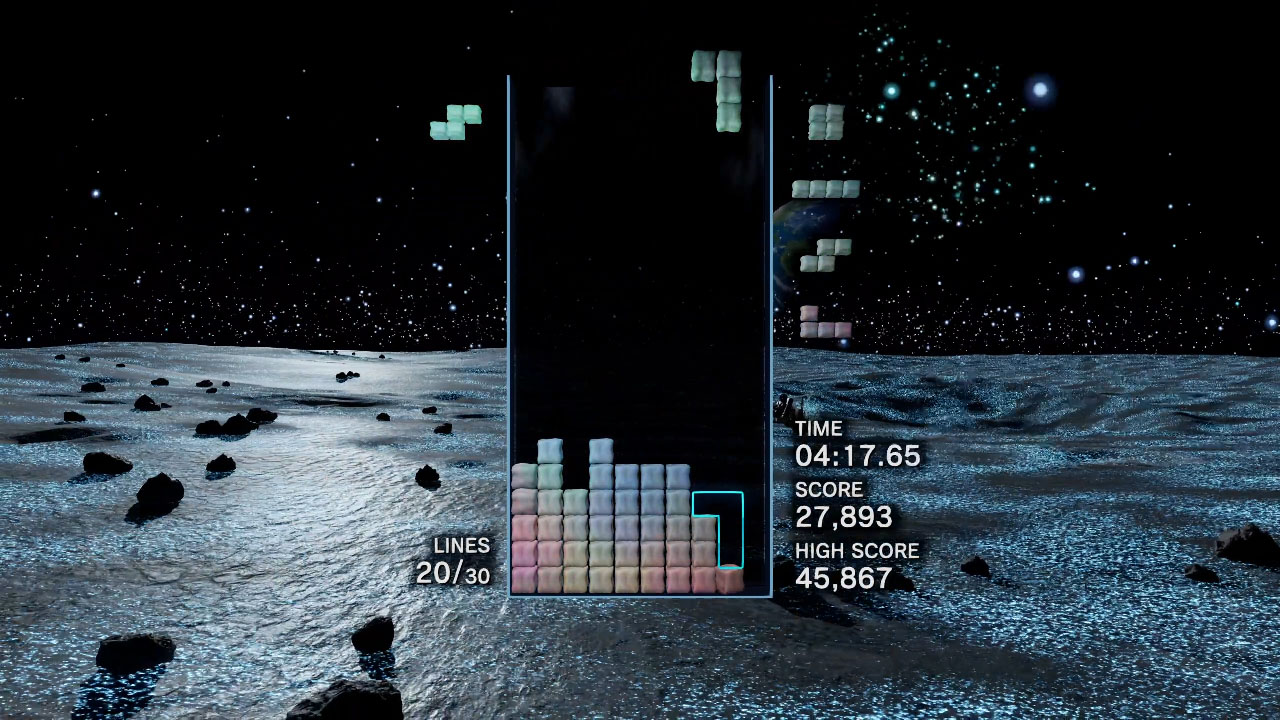

Tetris Effect’s beautiful, ephemeral levels allow players to get lost within the music and visuals. The appeal of Tetris Effect is to experience the titular phenomenon. TGM revitalizes some of Classic Tetris’ inherent mechanics while also emphasizing the speed and finesse of Modern Tetris. It recaptures the appeal of score-attack by applying a grade to player scores. The ultimate goal of TGM, then, is to become a grand master.

There’s a lot of design space to explore within Tetris. My upcoming video essay looks to evaluate and compare several Tetris titles’ design priorities and where they fit into the larger market. Much like the Tetris genre as a whole, its players are sensitive to changes made to the standard formula. The Tetris Guidelines have become so engrained into the culture and expected flow of play as to render the originating document a footnote in the iteration of Tetris.

Because these design expectations are constant, Tetris is a slowly shaped medium that struggles to innovate due to the demands of its property holder and players. Non-licensed Tetris titles are used as a comparison point of how Tetris can be meaningfully innovated when the shackles are let loose.

Tetris also provides a stellar talking point for future research projects about live-service games and how those titles iterate over time - often in a way that hurts the player experience and devalues the game’s original design intent. At the core of the issue, Tetris acts as an introduction to the larger conversation about the disposability of video games and how modern day practices are harming the ability for video games to be art.